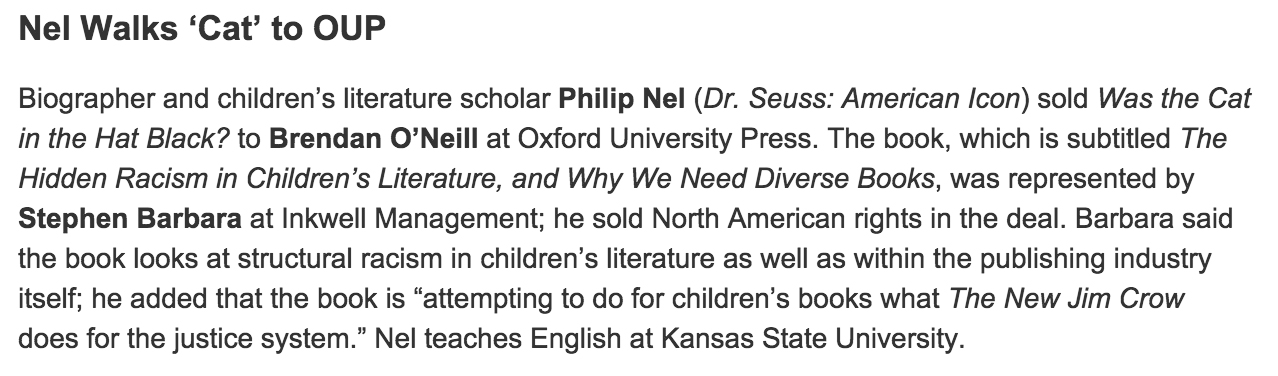

Here’s some news I’ve been itching to share: Oxford University Press will publish my next book, Was the Cat in the Hat Black?: The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature, and Why We Need Diverse Books. Also, this coming Monday, I will be turning in (to Oxford) the complete manuscript of the book. Though it’s too early to confirm a publication date, I’m hoping it will be out by late 2016.

No, the entire book is not about the Cat in the Hat, though Seuss’s famous feline features prominently in one chapter. The book is about different manifestations of structural racism in the world of children’s books: the subtle persistence of racial caricature, how anti-racist revisionism sustains racist ideas, invisibility as a form of racism, whitewashing young adult book covers, and institutional discrimination within the publishing industry. The book takes its title from the Seuss chapter (which looks at, among other things, the influence of blackface minstrelsy on the Cat) because several of his works illustrate how racism hides openly – indeed, thrives – in popular culture for young people. Since the hidden racism of children’s literature is my central theme, a Cat-in-the-Hat riff on Shelley Fisher Fishkin’s Was Huck Black? became the title.

No, the entire book is not about the Cat in the Hat, though Seuss’s famous feline features prominently in one chapter. The book is about different manifestations of structural racism in the world of children’s books: the subtle persistence of racial caricature, how anti-racist revisionism sustains racist ideas, invisibility as a form of racism, whitewashing young adult book covers, and institutional discrimination within the publishing industry. The book takes its title from the Seuss chapter (which looks at, among other things, the influence of blackface minstrelsy on the Cat) because several of his works illustrate how racism hides openly – indeed, thrives – in popular culture for young people. Since the hidden racism of children’s literature is my central theme, a Cat-in-the-Hat riff on Shelley Fisher Fishkin’s Was Huck Black? became the title.

Here’s my opening paragraph:

Fifty years after the Civil Rights Movement, we have a new civil rights crusade – the Black Lives Matter movement, inspired by the 2013 acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer, and galvanized by the 2014 Ferguson protests. Fifty years after Nancy Larrick’s famous “All-White World of Children’s Books” article (1965) asked where were the people of color in literature for young readers, the We Need Diverse Books campaign is asking the same questions. These two phenomena are related. America is again entering a period of civil rights activism because racism is resilient, sneaky, and endlessly adaptable. In other words, racism endures because racism is structural: it’s embedded in culture, and in institutions. One of the places that racism hides – and the best place to oppose it – is books for young people.

As the Publishers Weekly blurb says, Was the Cat in the Hat Black? is indeed an “attempt… to do for children’s books what The New Jim Crow does for the justice system.”

I realize that this is a tall order: Michelle Alexander’s book is both powerful and beautifully written. But this is indeed my aim. I want not just to get more people thinking about racism’s resilience in children’s literature. I want people to act. I want not merely to recognize the dire need for more children’s and young adult books that better represent the experiences of non-White people. I want people to join the movement for diverse books. So, rather than just conclude, Was the Cat in the Hat Black? ends with a call to action –Â “A Manifesto for Anti-Racist Children’s Literature.”

Finishing this book (on top of teaching, writing other things, grading, editing, and everything else) is one reason this blog has recently been a little quieter than usual. As regular or even irregular readers of Nine Kinds of Pie have likely already guessed, fragments of this work-in-progress have appeared here. My earliest (and admittedly flawed) thinking on what developed into Chapter Two started as “Can Censoring a Children’s Book Remove Its Prejudices?” Parts of an autobiographical post appear in the introduction. Indeed, I gave an earlier, article version of the title chapter its own blog post. Scattered here and there across the blog are glimpses of me thinking about racism in children’s literature. Many of these pieces will vanish when the blog does, but others – almost always in a significantly revised form – find their way into the book.

Finishing this book (on top of teaching, writing other things, grading, editing, and everything else) is one reason this blog has recently been a little quieter than usual. As regular or even irregular readers of Nine Kinds of Pie have likely already guessed, fragments of this work-in-progress have appeared here. My earliest (and admittedly flawed) thinking on what developed into Chapter Two started as “Can Censoring a Children’s Book Remove Its Prejudices?” Parts of an autobiographical post appear in the introduction. Indeed, I gave an earlier, article version of the title chapter its own blog post. Scattered here and there across the blog are glimpses of me thinking about racism in children’s literature. Many of these pieces will vanish when the blog does, but others – almost always in a significantly revised form – find their way into the book.

So, a hearty thanks to those who have read and commented here, answered my questions, offered feedback when I’ve presented portions of this work, or educated me via your books and articles. I’ve learned so much from all of you. (Hint: Look for your names in the book’s Acknowledgments!) I couldn’t have done it without you. Thank you.

Joe Kelly

mcliious

Joe S. Sanders

Daria

pragmaticmom

Philip Nel

Daria

Clem B

Philip Nel

Pingback: Extra Reading, for next Monday | Children's & YA Literature: Theory and Method

Shaun Baker

Philip Nel

William joyce

Fuck You

Philip Nel

Philip Nel

William Joyce

Philip Nel