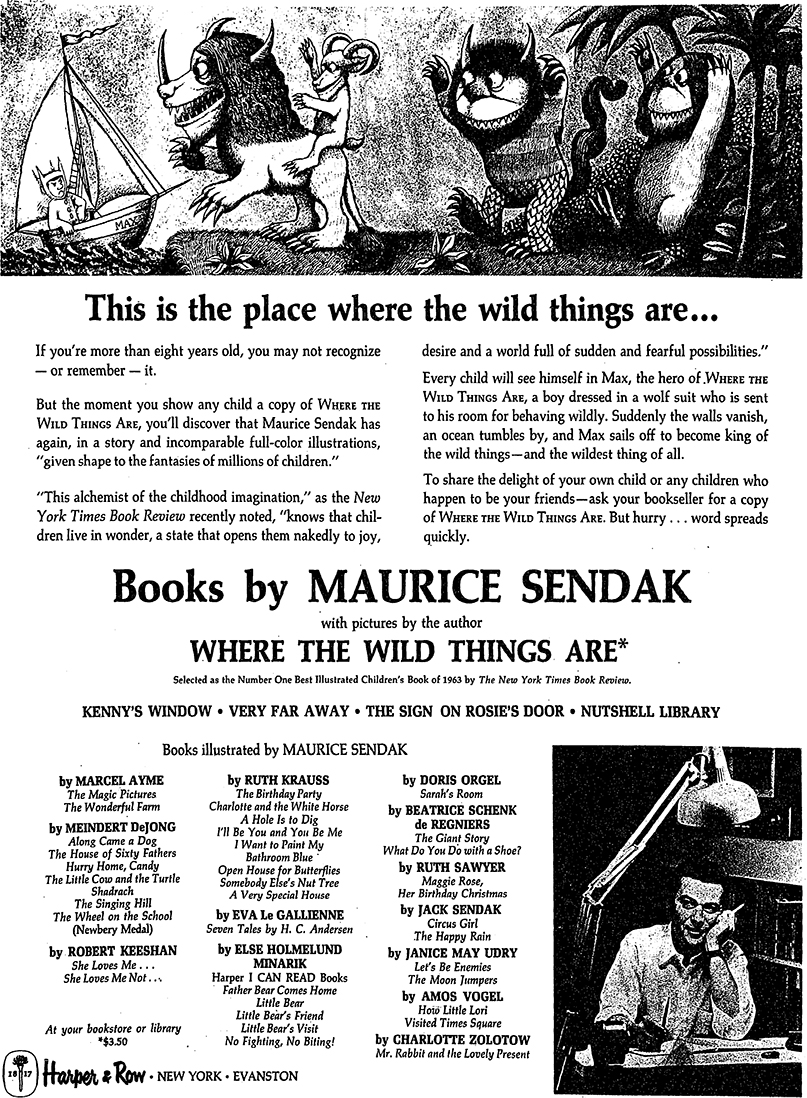

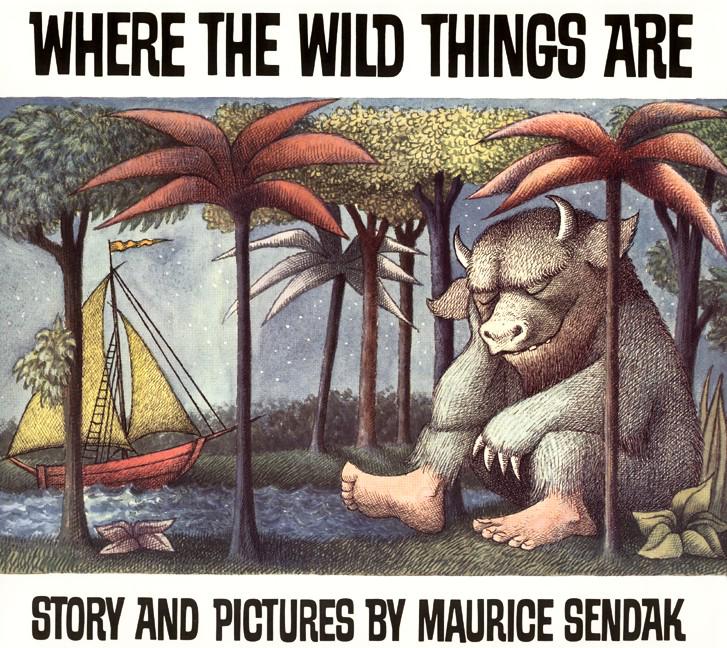

My fellow Niblings (Betsy Bird, Julie Walker Danielson, Travis Jonker) and I decided a few months ago that it’d be fun to coordinate some blog posts today in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of Where the Wild Things Are. It’s 50 years old, having been originally released in Fall 1963. After some research, we figured out that its release was in October of that year. Here’s my contribution.

Maurice Sendak’s work makes adults uncomfortable, and these adults then consequently worry about how children will feel. Will a Sendak book make children uncomfortable, too? they wonder. Or What sort of child does the Sendak book expect as its reader? Or, even, What is a child? The Sendak book that got us adults asking these questions is Where the Wild Things Are, published 50 years ago, in October 1963.

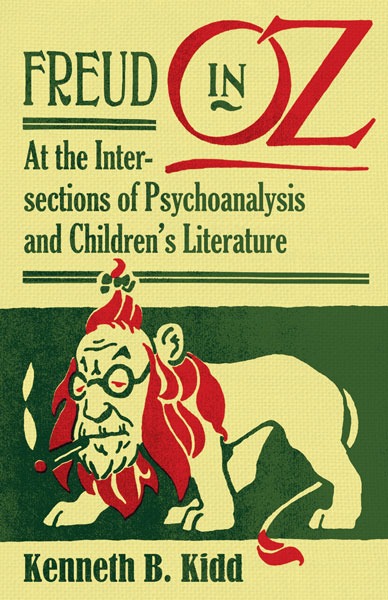

In his infamous 1969 Ladies Home Journal piece, Bruno Bettelheim – who had not then read Where the Wild Things Are (1963) – worried about the book’s effect on “the child.” As he said, “The basic anxiety of the child is desertion. To be sent to bed alone is one desertion, and without food is the second desertion. The combination is the worst desertion that can threaten a child” (48). Yet, as Maria Tatar points out, Bettelheim shares Sendak’s view that reading stories about childhood anxieties can be potentially therapeutic, a way for children to (in Sendak’s words) tame wild things through fantasy. One of our foremost scholars of fairy tales (the darkest genre within children’s literature, and a genre originally not for children at all), Tatar herself wonders whether Dear Mili (1988) – Sendak’s version of a Wilhelm Grimm tale – is suitable for children. “There are good reasons why we do not start out stories with descriptions of widows who have lost all their children but one or end them with images of mother and daughter lying down and dying,” she writes, and then partially disavows this criticism in her next sentence: “This is not to say that children should be shielded from descriptions of material hardships and death, only that they are not necessarily better off when entertained with stories that reflect or take as their point of departure the social and cultural realities of an age other than their own” (220).  In an essay on allegory in Sendak, Geraldine DeLuca considers In the Night Kitchen (1970) “true to a child’s experience” but Outside Over There (1981) unsuitable for children because “we – particularly children – are left at the end of this work with too much pain” (14, 22). Kenneth Kidd, whose chapter from Freud in Oz (2011) is one of the sharpest analyses of Sendak, also codifies his notion of childhood in contrast with his assessment of Sendak’s. As he writes, “While Sendak neither romanticizes the child nor minimizes the child’s experiences with trauma, his makeover of monstrosity amounts to a kind of gentling of the child rather than a celebration of childhood’s radical alterity” (131). In other words, for Kidd, childhood is a state of radical alterity, but Sendak minimizes that, offering instead (as Kidd says later) “the domestication of wildness” (135).

In an essay on allegory in Sendak, Geraldine DeLuca considers In the Night Kitchen (1970) “true to a child’s experience” but Outside Over There (1981) unsuitable for children because “we – particularly children – are left at the end of this work with too much pain” (14, 22). Kenneth Kidd, whose chapter from Freud in Oz (2011) is one of the sharpest analyses of Sendak, also codifies his notion of childhood in contrast with his assessment of Sendak’s. As he writes, “While Sendak neither romanticizes the child nor minimizes the child’s experiences with trauma, his makeover of monstrosity amounts to a kind of gentling of the child rather than a celebration of childhood’s radical alterity” (131). In other words, for Kidd, childhood is a state of radical alterity, but Sendak minimizes that, offering instead (as Kidd says later) “the domestication of wildness” (135).

While a good deal of literary criticism reveals as much about the critic as it does about the work, Maurice Sendak’s work is especially adept at calling forth our emotional responses. Or, to put this another way, the effect of Sendak’s art is affect. His books are good at making us feel. So, while appeals to emotion or to vaguely defined ideas of “the child” can mar scholarship of children’s literature, Maurice Sendak’s work actually requires us to venture into these potentially risky areas.

As I argue in an essay forthcoming in the January 2014 issue of PMLA, Sendak’s affective aesthetic derives from several sources. (What you are reading now includes only what I had to cut from that essay, plus a few new ideas.)

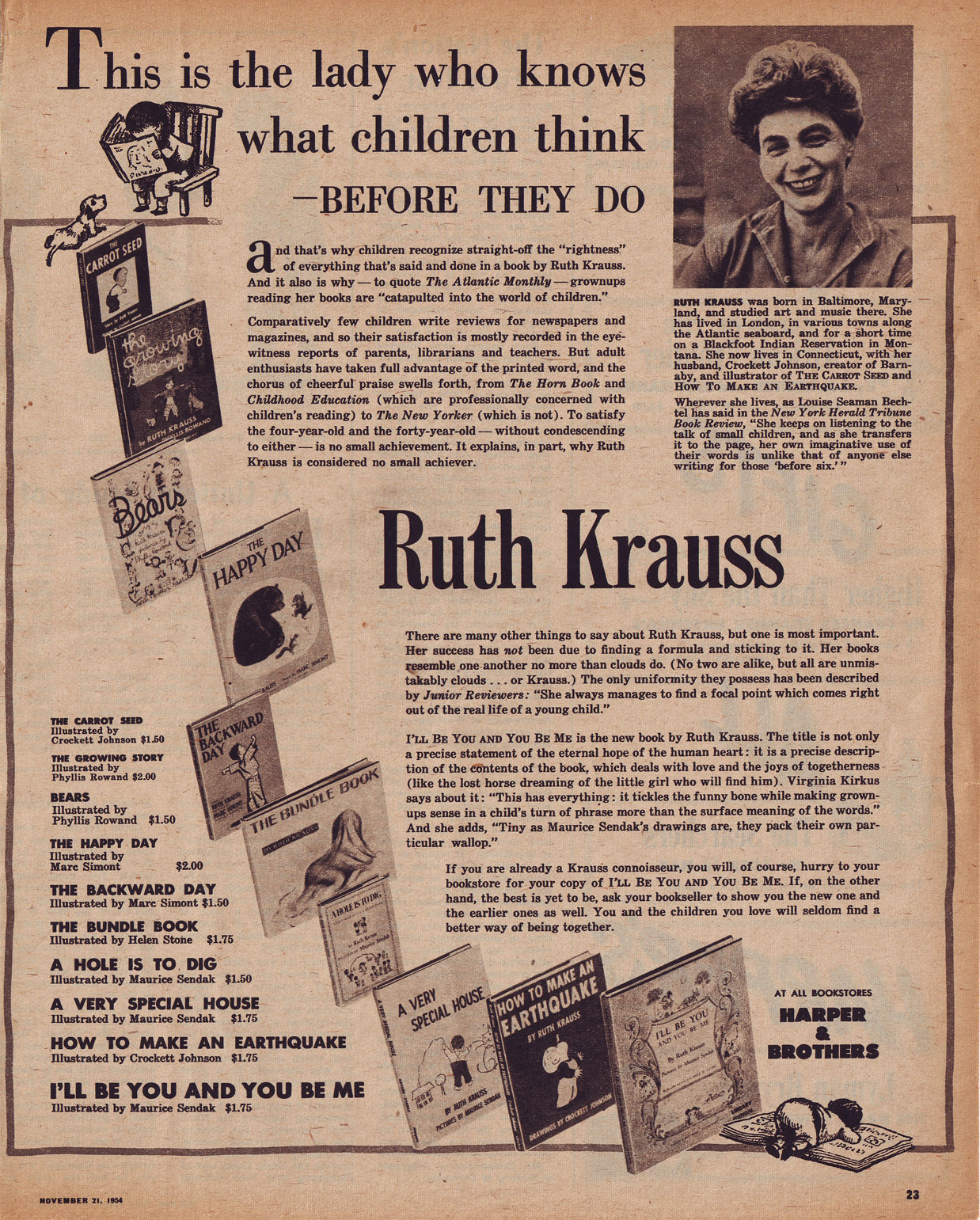

Part I. A Book is to Feel: Ruth Krauss’s Influence

A major source is Ruth Krauss. Sendak illustrated eight of her books between 1952 and 1960, often spending his weekends at the home of Krauss and her husband Crockett Johnson – a period of time Sendak has referred to as his apprenticeship into the world of children’s books. One thing he learned from her is to embrace the wildness of children. As Sendak told me in a 2001 interview, “Max has his roots in Ruth Krauss. You know, her phrase that kids were allowed to be as cruel and maniacal as she knew they were. Studying them at Bank Street, she knew what monstrosities children are.”

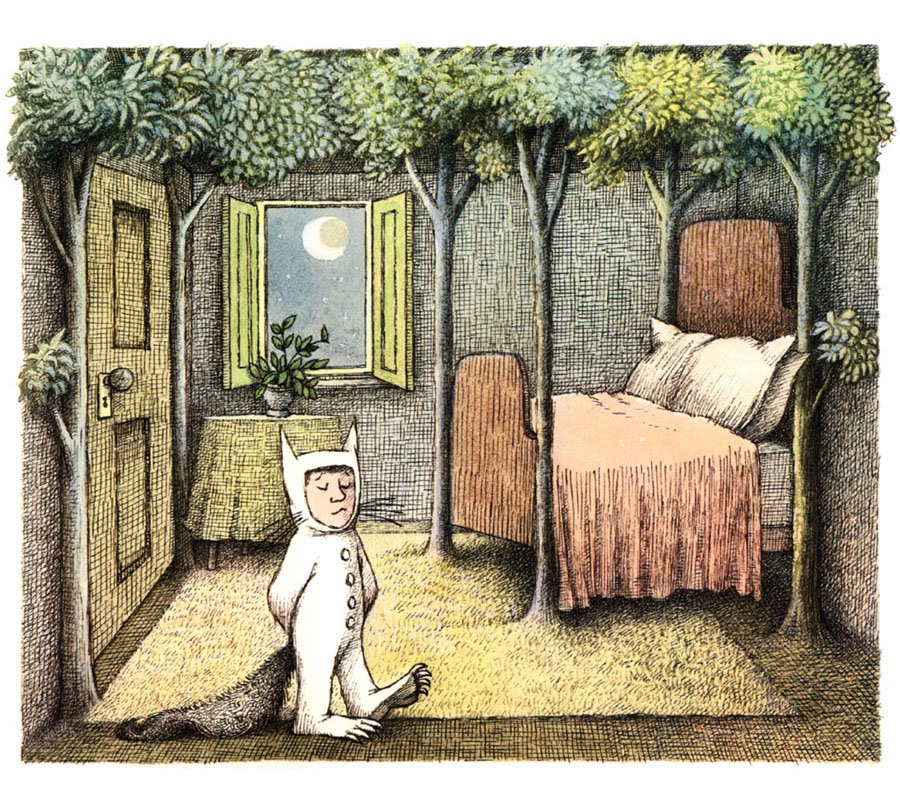

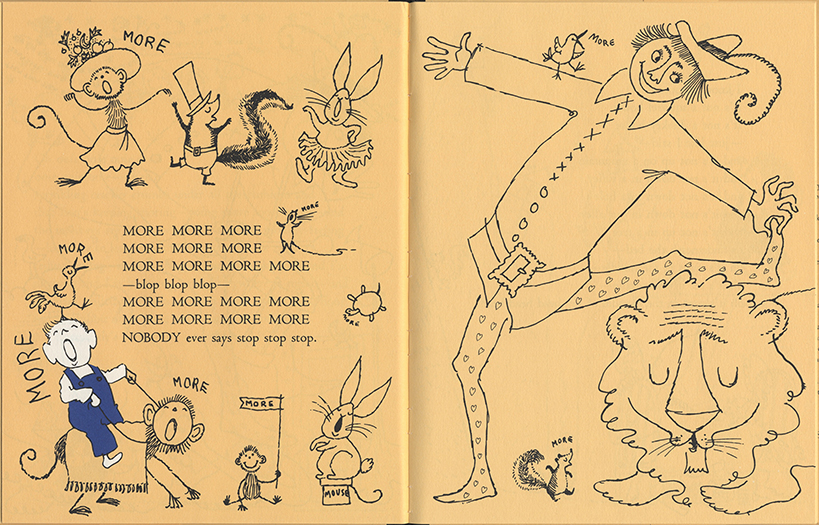

Indeed, Ruth Krauss’s A Very Special House (1953) – the second of her books illustrated by Sendak – might be read as the first version of Where the Wild Things Are. As George Bodmer puts it, each book has “a solitary child who falls into fantastic adventures that spring up from his thoughts” (181). The unnamed child of A Very Special House climbs the chairs, jumps on the bed, and draws on the walls, allowing him (through his art) to bring home “a turtle / and a rabbit and a giant / and a little dead mouse / – I take it everywheres – / and some monkeys and some skunkeys / and a very old lion.” Though the boy wears overalls throughout, in one scene he dons a white smock and a “Valkyries” style horned helmet, a costume that echoes the horns on Max’s white wolf suit. In Where the Wild Things Are, Max is comparably transgressive. He hangs his teddy bear, hammers a nail into the wall, chases the dog with a fork, imagines his room into a forest, and sails off to the land of the wild things – who, like the giant and old lion in A Very Special House, are both much larger than he is and willing to be ruled by him.

Contemporary reviews also noted both books’ celebration of rule-breaking. The Atlantic Monthly’s reviewer praised A Very Special House’s “unorthodox” qualities and suggested that, while it is “no handbook for deportment,” “in the blowing-off-steam department, it deserves an award” (qtd in Nel 137). Wild Things’ reception was more mixed, but, writing of Max’s “fantasy of rage,” the New York Times noted that the book “projects, releases, and masters a universal experience for the child” (qtd. in Lanes 107). Though neither child faces punishment for his unruliness, there’s more conflict in Wild Things than in the earlier book: in A Very Special House, “NOBODY ever says stop stop stop”; in Wild Things, Max’s mother sends him to bed without supper, though ultimately relents – Max finds “his supper waiting for him” at the end.

One reason that people respond to Max as if he and his adventures were real is that Sendak also learned from Krauss to “keep it real.” As he said, Krauss’s “The Carrot Seed, with not a word or a picture out of place, is dramatic, vivid, precise, concise in every detail. It springs fresh from the real world of children, the Bank Street world of listening to children and recording and re-creating their startling speech patterns and curious, pragmatic thinking processes” (“Ruth Krauss and Me” 286). He’s wrong about the book’s composition: The Carrot Seed (1945) derived from Krauss’s imagined conversation with a 5-year-old neighbor. But he’s right about Krauss’s compositional methods during the period she worked with him. Beginning with A Hole Is to Dig (the first book of hers that he illustrated), Krauss used children’s spontaneous utterances in her books.

As Kenneth Kidd has pointed out, Sendak’s own experience in psychoanalysis (which he entered at roughly the same time he began working on Krauss’s books) also played a role in his art’s realism, as it helped him both access his childhood emotions and use them in his work: “His books also resemble the child-adult playwork practiced by child analysts, which is hardly surprising since Sendak imitates some of their techniques. Sendak, in short, is the consummate picturebook psychologist” (105).

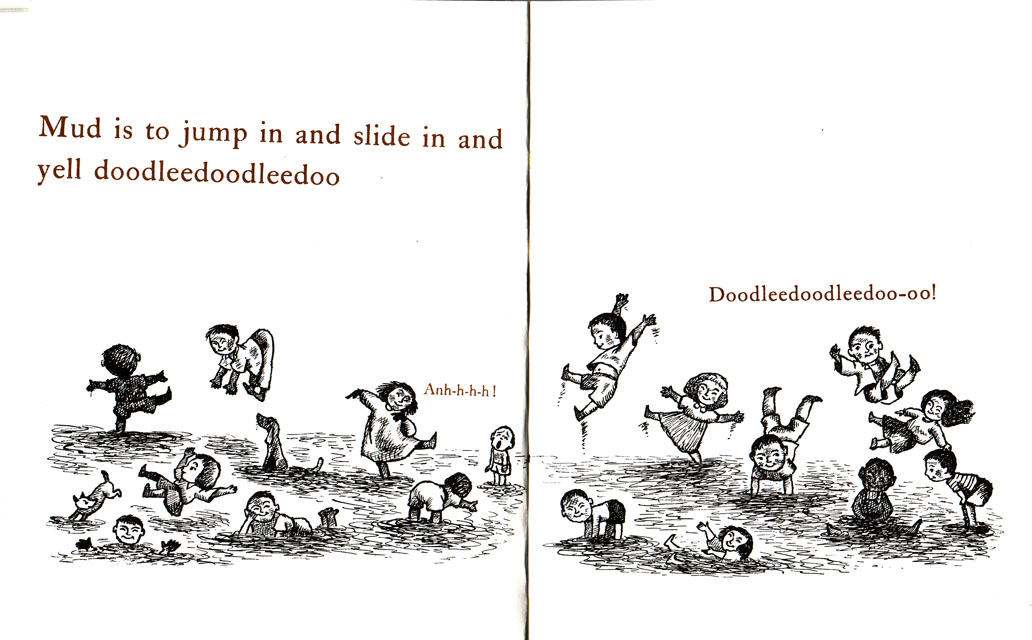

Krauss, who also saw a psychologist, also taught Sendak not to repress his emotions. As he told me in that same 2001 interview, she taught him how to curse. Most interviews with Sendak excise the cursing, but his use of profanity was fluent, even exuberant. His and Krauss’s child characters don’t say “fuck” (as Sendak did), but they do shout at us. In A Hole Is to Dig, a two-page spread of sixteen muddy children inform us: “Mud is to jump in and slide in and yell doodleedoodleedoo!” In the Krauss-Sendak collaboration I’ll Be You and You Be Me (1954), an older child stands between two warring smaller children, and asks one “Is there something you want to say to Dickie?” With his fist raised and an angry eyebrow slanted downward, Dickie answers, “Yes! I want to put him in the garbage can.” In his own work, Sendak also conveys the understanding that using a large, loud voice can be a small person’s main source of power. Where the Wild Things Are alleges that Max tames the wild things “with the magic trick of staring into their yellow eyes without blinking once,” but that “trick” begins with Max’s voice. He shouts, “BE STILL!” And they obey.

The impulse to draw from real children also grants Sendak access to a wide range of childhood experiences. Though Max has come to symbolize the Sendakian child, there is no single Sendakian child, no unified field theory of “childhood” that emerges in his work. Nor is there any unified style – in part because Ursula Nordstrom (his editor) and Krauss insisted that he try different approaches. As he told me, “I had to keep changing styles, and this is something Ruth did too. Beating me over the back not to become a stylist.” I replied, “Don’t fall into a rut.” He said, “Yeah. Don’t get a style where you’re always recognizable.” So, as Leonard Marcus notes, for Sendak, “the visual manner and medium of a book mattered far less than the emotional truth it had to tell” (19).

Part II. The Emotional Landscape of Childhood

Though drawing on his own early childhood, Sendak managed to create books that resonated (and continue to resonate) with readers’ sense of their own childhoods. He understood that, as Mo Willems observed just after Sendak’s death, “However life changes for children, and how childhood is defined over generations, there’s still an inner life. Everything that you do as a child is for the first time. So, when you fail – even by walking and tripping – that’s your first failure. And it’s massive” (Andersen). Amplifying parts of his own particular experience, Sendak was able to convey something from this shared “inner life,” something that felt universal. This feeling is one reason why critics tend to read his work as saying something definitive about “the child” or childhood. We recognize experiences from our childhoods in the art inspired by Sendak’s.

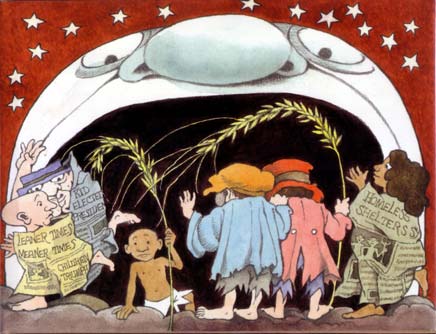

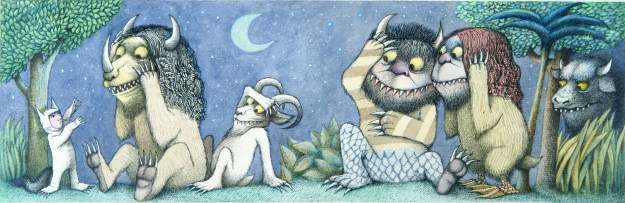

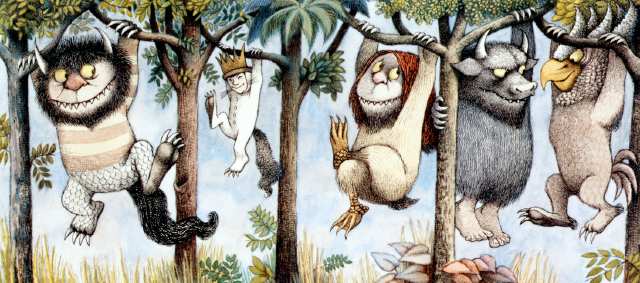

Granting us access to that “inner life,” the faces of Sendak’s characters telegraph their emotions. In Where the Wild Things Are, Max’s face conveys a full range of emotions – anger (at his mother), joy (as he sets sail on the boat), imperiousness (as he becomes king of the wild things), and melancholy (when he longs for home). When he gets home, his light smile and half-closed eye conveys contentment. But many of Sendak’s later books do not end quite so happily. As the rat tries to carry him off stage right, the “poor little kid” in We’re All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy (1993) has a black eye, and his mouth open to cry out – likely the word “help,” the sole thing he utters in the book (five times in all). To the left of him, “THE MOON’S IN A FIT”: an angry-faced moon has lifted Jack and Guy up by their newspaper robes; their feet dangling over the ground and their mouths downturned, the boys’ eyes look out at the reader, uncertainly. Just left of them, the other homeless children flee off to the left of the page, defying the typical left-to-right movement across the page. It’s an unsettling scene in a book that ends with children only temporarily safer, sleeping in a sidewalk shantytown. The ending of Outside Over There is ambivalent at best. Armed only with a “wonder horn,” Ida travels into “outside over there,” defeats the goblins with her music, rescues her younger sister and brings her home to mother. However, as playwright Tony Kushner observes, “The reunion of Ida and her sister with their mother at the end of Outside is reassuring, though … Sendak has taken pains to limit that comfort”: the baby is tearful, and Ida and her mother “look resigned rather than joyful at the news that their absent husband/father will return ‘one day,’ which is not, of course, especially reassuring news – when, exactly?” (The Art of Maurice Sendak Since 1980 22).

Granting us access to that “inner life,” the faces of Sendak’s characters telegraph their emotions. In Where the Wild Things Are, Max’s face conveys a full range of emotions – anger (at his mother), joy (as he sets sail on the boat), imperiousness (as he becomes king of the wild things), and melancholy (when he longs for home). When he gets home, his light smile and half-closed eye conveys contentment. But many of Sendak’s later books do not end quite so happily. As the rat tries to carry him off stage right, the “poor little kid” in We’re All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy (1993) has a black eye, and his mouth open to cry out – likely the word “help,” the sole thing he utters in the book (five times in all). To the left of him, “THE MOON’S IN A FIT”: an angry-faced moon has lifted Jack and Guy up by their newspaper robes; their feet dangling over the ground and their mouths downturned, the boys’ eyes look out at the reader, uncertainly. Just left of them, the other homeless children flee off to the left of the page, defying the typical left-to-right movement across the page. It’s an unsettling scene in a book that ends with children only temporarily safer, sleeping in a sidewalk shantytown. The ending of Outside Over There is ambivalent at best. Armed only with a “wonder horn,” Ida travels into “outside over there,” defeats the goblins with her music, rescues her younger sister and brings her home to mother. However, as playwright Tony Kushner observes, “The reunion of Ida and her sister with their mother at the end of Outside is reassuring, though … Sendak has taken pains to limit that comfort”: the baby is tearful, and Ida and her mother “look resigned rather than joyful at the news that their absent husband/father will return ‘one day,’ which is not, of course, especially reassuring news – when, exactly?” (The Art of Maurice Sendak Since 1980 22).

Of course, as Sendak observed, “Children know about death and sorrow and sadness” (Zarin). And attempts to protect them from books that address dark subjects may underestimate them. Sendak again: “We should let children choose their own books. What they don’t like they will toss aside. What disturbs them too much they will not look at. And if they look at the wrong book, it isn’t going to do them that much damage. We treat children in a peculiar way, I think. We don’t treat them like the strong creatures they really are” (Lanes 106).

Sendak was wise to defend the right to tell stories that may upset us and Bettelheim was unwise to criticize a book he had never read. (Sendak never forgave him for that, either. In conversation, he referred to him derisively as “Benno Brutal-heim.”) However, Bettelheim is also not wrong to suggest that Where the Wild Things Are may upset young readers. I was one of those children who found the book terrifying, though not for the reasons Bettelheim mentioned. The book frightened me because I knew it was true: The boundary between real and imagined worlds was perilously fragile. When the lights went out, my bedroom could very easily turn into a jungle, bringing me far too close to the land of the wild things, who “gnashed their terrible teeth and rolled their terrible eyes and showed their terrible claws.” As an adult, I realize that the wild things’ googly eyes make them look more goofy than threatening. As a child, I focused only on their size, their talon-like claws, and their sharp teeth. As a result, I read Where the Wild Things Are once. After that, I kept my distance. Mine may be a minority opinion. During his childhood, Mo Willems thought it “an empowering book” (Andersen). The vast majority of my students recall enjoying the book during their childhoods. But the book does have the power to frighten.

Sendak was wise to defend the right to tell stories that may upset us and Bettelheim was unwise to criticize a book he had never read. (Sendak never forgave him for that, either. In conversation, he referred to him derisively as “Benno Brutal-heim.”) However, Bettelheim is also not wrong to suggest that Where the Wild Things Are may upset young readers. I was one of those children who found the book terrifying, though not for the reasons Bettelheim mentioned. The book frightened me because I knew it was true: The boundary between real and imagined worlds was perilously fragile. When the lights went out, my bedroom could very easily turn into a jungle, bringing me far too close to the land of the wild things, who “gnashed their terrible teeth and rolled their terrible eyes and showed their terrible claws.” As an adult, I realize that the wild things’ googly eyes make them look more goofy than threatening. As a child, I focused only on their size, their talon-like claws, and their sharp teeth. As a result, I read Where the Wild Things Are once. After that, I kept my distance. Mine may be a minority opinion. During his childhood, Mo Willems thought it “an empowering book” (Andersen). The vast majority of my students recall enjoying the book during their childhoods. But the book does have the power to frighten.

However, that power is what makes Where the Wild Things Are such a great book. That power is what has made it endure, and is what helped to establish Sendak not just as one of the great artists but as one of the great interpreters of childhood. Sendak understood the sometimes scary complexities of being a child. He had the courage to convey those truths both in his work, and in his role as spokesperson for both children’s literature and children themselves. As Kidd points out, by the middle of the twentieth century, the picture book author-illustrator began to assume the role of “something like an expert on childhood, even a lay child analyst,” whose expertise “came from proximity to childhood” (123). For example, those who do not study, read or write children’s literature were a little scandalized by Sendak’s appearance on the Colbert Report, during which the author suggested that the mouse of You Give a Mouse a Cookie “should be exterminated,” claimed that “Most books for children are very bad,” and conceded that it was “a miracle that I have lived this long without having destroyed a person.” But those of us who do study, read, or write children’s literature laughed and applauded Sendak’s grumpy wisdom. We thought: That “Mouse” book is so relentlessly average – good riddance! And: Children’s literature is art! And: He speaks for us!

Whether we knew him personally or not, he was a giant. He had come to define the field of children’s literature. So, when Sendak passed away in May last year, we all gathered on the web to mourn his passing and celebrate his work. As Daniel Handler (best known by his pseudonym Lemony Snicket) said, “It’s almost impossible to overstate his importance. He’s a North Star in the firmament of anyone who makes children’s books, in particular for his dark and clear-eyed view of the world that was kindred to me when I was in kindergarten and kindred to me now. He gives neither the comfort nor the horror of sentimentality” (Italie). Novelist Gregory Maguire, graphic novelist Art Spiegelman, picture-book legend Tomi Ungerer, scholar Maria Tatar and dozens of others all wrote or drew tributes. Neil Gaiman wrote two. As Kenneth Kidd noted at the time, “my Facebook newsfeed is a virtual wake” (“Goodbye, Maurice”).

Sendak has sailed off on the journey from which none return, but his books continue to provide safe passage for us to explore the land of the wild things. The creatures of his imagination speak to the realities of our world – a world in which children shout at adults, get lonely, and dance the wild rumpus. A world in which they are misunderstood, frightened, and (we hope) loved by their caregivers. It’s a wild world, and it’s getting wilder every day.

Works Cited

Andersen, Kurt. “Mo Willems remembers author Maurice Sendak” Studio 360 with Kurt Andersen 13 May 2012 <http://www.pri.org/stories/arts-entertainment/books/mo-willems-remembers-author-maurice-sendak-9853.html>.

Bettelheim, Bruno. “The Care and Feeding of Monsters.” Ladies Home Journal Mar 1969: 48.

Bodmer, George. “Ruth Krauss and Maurice Sendak’s Early Illustration.” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 11.4 (Winter 1986-87): 180-183

DeLuca, Geraldine. “Exploring the Levels of Childhood: The Allegorical Sensibility of Maurice Sendak.” Children’s Literature 12 (1984): 3-24.

“Grim Colberty Tales, Part 1.” The Colbert Report 24 Jan. 2012. <http://www.colbertnation.com/the-colbert-report-videos/406796/january-24-2012/grim-colberty-tales-with-maurice-sendak-pt–1>.

“Grim Colberty Tales, Part 2.” The Colbert Report. Comedy Central. 25 Jan. 2012. <http://www.colbertnation.com/the-colbert-report-videos/406902/january-25-2012/grim-colberty-tales-with-maurice-sendak-pt–2>.

Grimm, Wilhelm. Dear Mili. Translated by Ralph Manheim with pictures by Maurice Sendak. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux (Michael di Capua Books), 1988.

Italie, Halel. “Writers Remember Maurice Sendak.” Chicago Sun-Times 10 May 2012: <http://www.suntimes.com/entertainment/books/12430172-421/writers-remember-maurice-sendak.html>.

Kidd, Kenneth B. Freud in Oz: At the Intersections of Psychoanalysis and Children’s Literature. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

—. “Goodbye, Maurice. And Thank You.” University of Minnesota Press Blog. 10 May 2012: <http://www.uminnpressblog.com/2012/05/kenneth-b-kidd-goodbye-maurice-and.html>.

Krauss, Ruth. A Hole Is to Dig. Pictures by Maurice Sendak. 1952. New York: HarperTrophy (HarperCollins), 1989.

—. A Very Special House. Pictures by Maurice Sendak. 1953. New York: HarperCollins, 1981.

—. I’ll Be You And You Be Me. Pictures by Maurice Sendak. 1954. HarperCollins, 1982.

—. The Carrot Seed. Illustrated by Crockett Johnson. 1945. New York: HarperFestival, 1993.

Kushner, Tony. The Art of Maurice Sendak: 1980 to the Present. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2003.

Lanes, Selma G. The Art of Maurice Sendak. 1980. New York: Abradale Press/Harry N. Abrams, 1993.

Marcus, Leonard S., editor. Maurice Sendak: A Celebration of the Artist and His Work. New York: Abrams, 2013.

Nel, Philip. Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children’s Literature. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, September 2012.

—. Telephone interview with Maurice Sendak. 22 June 2001.

Numeroff, Laura Joffe. If You Give a Mouse a Cookie. Illustrated by Felicia Bond. New York: HarperCollins, 1985.

Sendak, Maurice. In the Night Kitchen. 1970. HarperCollins, 1995.

—. Outside Over There. New York: HarperCollins, 1981.

—. “Ruth Krauss and Me: A Very Special Partnership.” The Horn Book Magazine 70.3 (May-June 1994): 286-90.

—. We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy. New York: HarperCollins, 1993.

—. Where the Wild Things Are. 1963. HarperCollins, 1988.

Tatar, Maria. “Wilhelm Grimm/Maurice Sendak: Dear Mili and the Literary Culture of Childhood.” The Reception of Grimms’ Fairy Tales: Responses, Reactions, Revisions. Ed. Donald Haase. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1993. 207-229.

“Uncensored – Maurice Sendak Tribute & ‘I Am a Pole (And So Can You!)’ Release.” The Colbert Report 8 May 2012. <http://www.colbertnation.com/the-colbert-report-videos/413972/may-08-2012/uncensored—maurice-sendak-tribute—-i-am-a-pole–and-so-can-you—-release>.

Zarin, Cynthia. “Not Nice.” New Yorker 17 Apr. 2006. Literary Reference Center. Web. 2 July 2013.

A different variation on the argument presented above will appear as “Wild Things, I Think I Love You: Maurice Sendak, Ruth Krauss, and Childhood” in PMLA 129.1 (Jan. 2014).

The Niblings on Where the Wild Things Are at 50

- Betsy Bird,”Re-Sendakify Sendak Project: The Results” at Fuse #8.

- Julie Walker Danielson, “Making Mischief of One Kind or Another … for Fifty Years” at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast.

- Travis Jonker, “Books on Film: Where the Wild Things Are” at 100 Scope Notes.

- Philip Nel, “It’s a Wild World: Maurice Sendak, Wild Things, and Childhood” at Nine Kinds of Pie (Just scroll up!)

More on Sendak (mostly on this blog)

- Annotating My Brother’s Book: Some initial thoughts on Sendak’s use of Blake’s pictorial language. A guest post by Mark Crosby. Blake scholar Mark Crosby shows us how Blake’s work illuminates My Brother’s Book.

- The Most Wild Thing of All: Maurice Sendak, 1928-2012. My tribute to Sendak, including extracts from an (otherwise unpublished) interview I did with him, back in 2001. At the bottom of the post: links to many other tributes and obituaries from around the web.

- The King of the Wild Things Is Dead. Long Live the King. Maurice Sendak (1928-2012). My obituary for Sendak, which ran in the Comics Journal. A longer version appears as the introduction to Gary Groth’s interview, in the latest print issue.

- Tributes to Maurice Sendak: Artists Respond. In the wake of Sendak’s passing, many people created visual tributes. These are a few.

- Maurice Sendak, 1928-2012. The Horn Book‘s tribute includes links to interviews and articles.

- Eat, Drink, and Be Merry. My review of Sendak’s Bumble-Ardy.

- Maurice Sendak, Uncensored. A few thoughts on (and quotations from) Gary Groth’s Comics Journal interview.

- In or Out?: Crockett Johnson, Ruth Krauss, Sexuality, Biography. In which I meditate on how to address (or not) Maurice Sendak’s sexuality in my biography of Johnson and Krauss.

- The Maurice Sendak tag will take you to other posts on this blog.

Pingback: Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast » Blog Archive » Making Mischief of One Kind or Another … For Fifty Years