In his foreword to My Brother’s Book (2012), Stephen Greenblatt suggests that Shakespeare is the major influence on Maurice Sendak’s final competed work. But Blake loomed much larger in Sendak’s visual imagination. He collected rare Blake manuscripts, drawings, watercolors, illuminated books, and prints, read biographies of Blake, and studied his art and poetry. In this series of annotations (below), Blake scholar Mark Crosby shows us how Blake illuminates Sendak’s My Brother’s Book.

In terms of the visual narrative trajectory, Sendak reconfigures aspects of Blake’s visual language to chart the transition from the realm of innocence to the harsh world of experience (a transition that is, for Blake, always marked by some form of loss).

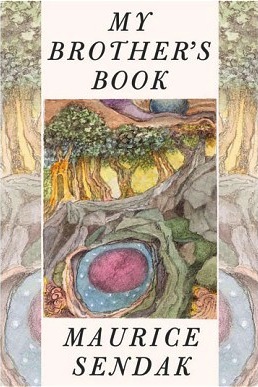

Front Cover:

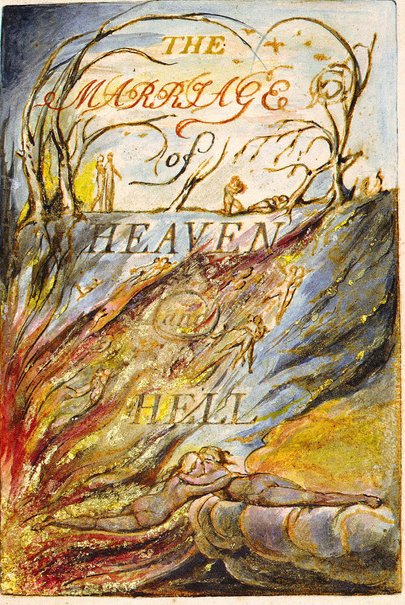

Sendak juxtaposes the beautiful, a woodland scene possibly atop a hill, with the sublime of a subterranean cavern or hollow beneath that looks out on a field of stars surrounding a red sphere. The vignette not only invokes Blake’s frequent juxtaposition of pastoral landscapes with the (subterranean) sublime, such as the title page of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, but also introduces the key visual motifs of stars and red sphere (sun?) that recur throughout Sendak’s book. Both motifs are conspicuous in Blake’s pictorial language.

|

|

William Blake, Title-page, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, copy H (1790-3) |

Maurice Sendak, My Brother’s Book (2012): cover |

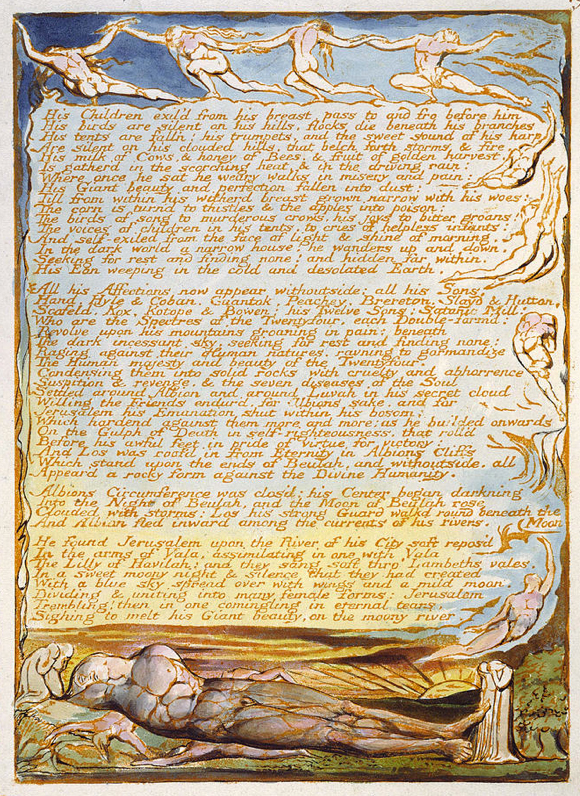

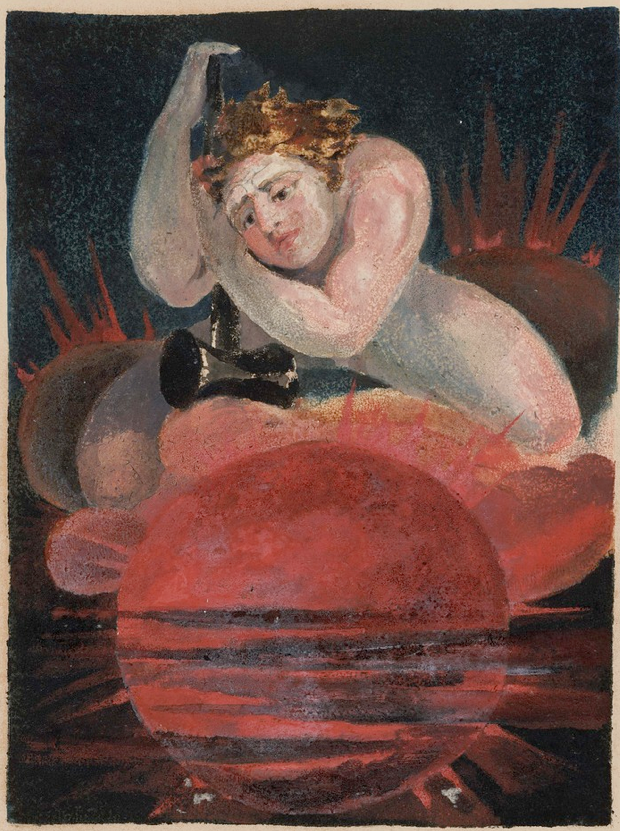

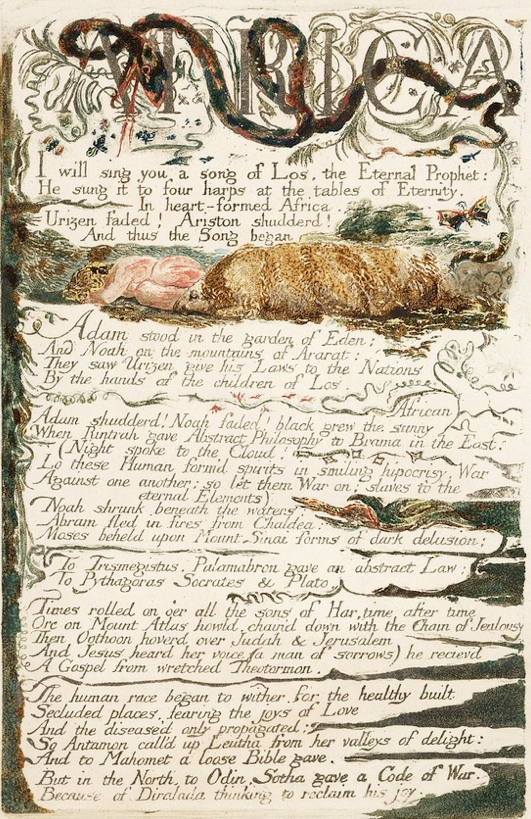

Blake deploys spheres of differing sizes throughout his pictorial work. In illuminated books such as The (First) Book of Urizen, they often represent the primordial (material) state of the titular Urizen, watched over by Los – the fallen form of Urthona, who in Blake’s mythopoetic system represents the imagination. (Many critics interpret Los as Blake’s poetic/pictorial avatar).

Blake, Plate 8, Song of Los, copy A (1795) |

Blake, Plate 11, The Book of Urizen, copy A (1794) |

In these instances, the spheres have a negative charge as they are objects of containment. In Blake’s longest illuminated book, Jerusalem, Blake uses spheres more positively as sources of light.

|

|

Blake, Plate1, Song of Los, (1795) |

Blake, Plate 97, Jerusalem (c. 1820) |

Frontispiece:

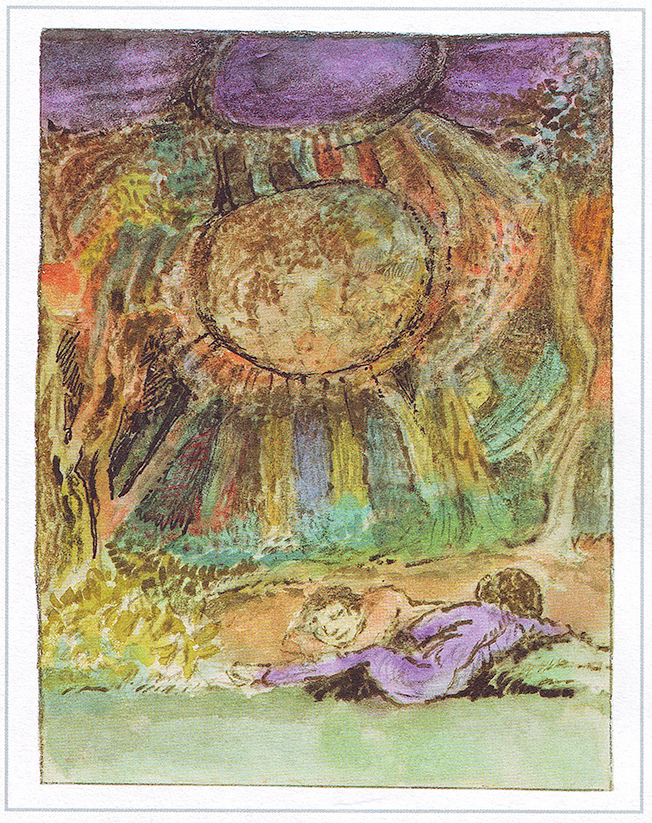

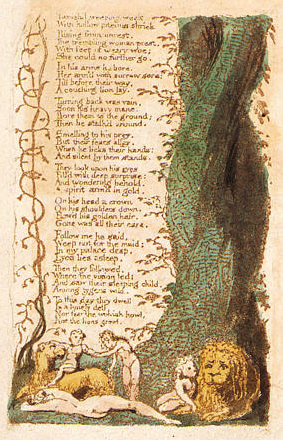

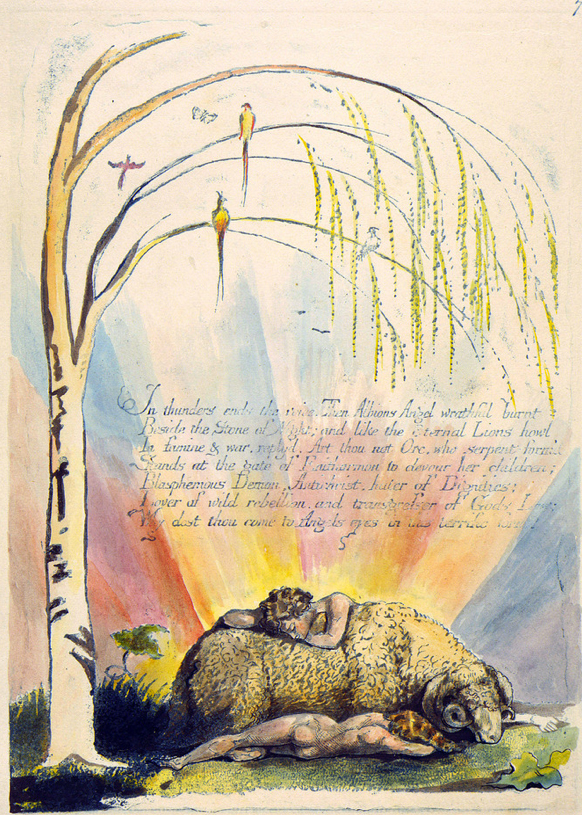

Sendak’s depiction of two slumbering, clothed males in a pastoral setting under a radiating sun calls to mind Blake’s positive use of sphere imagery. The sleeping brothers, Jack and Guy, have a number of visual referents in Blake. When depicted in a pastoral setting, Blake’s sleeping figures are sometimes associated with animals (sheep, lions) such as Songs of Innocence, America A Prophecy and The Song of Los. In Blake’s visual language, these images represent the realm of innocence, where the ideals of play, spontaneity, and intimacy with nature haven’t yet been corrupted. Sendak’s use of these Blakean motifs in the frontispiece similarly suggests that the slumbering brothers inhabit a pre-lapsarian realm, although they are clothed unlike many of Blake’s pre-lapsarian figures.

|

|

Blake, America A Prophecy |

Sendak, My Brother’s Book (2012): frontispiece |

|

|

Blake, The Song of Los |

Blake, Songs of Innocence |

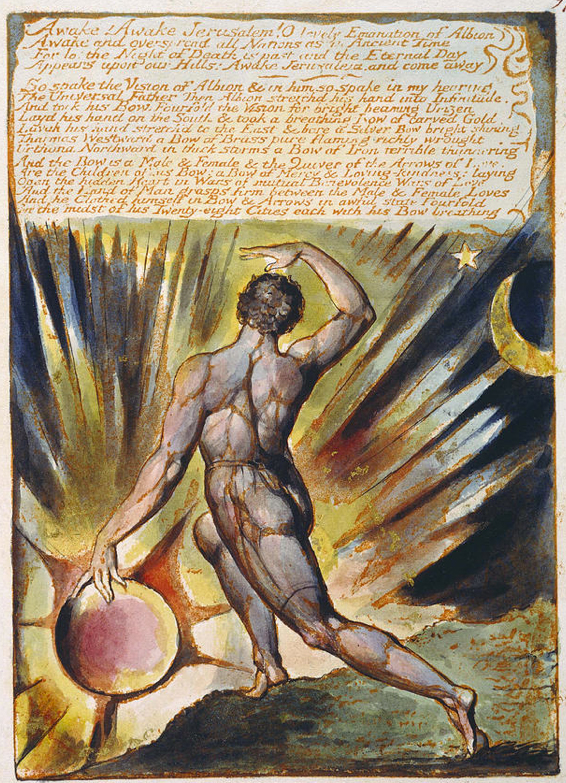

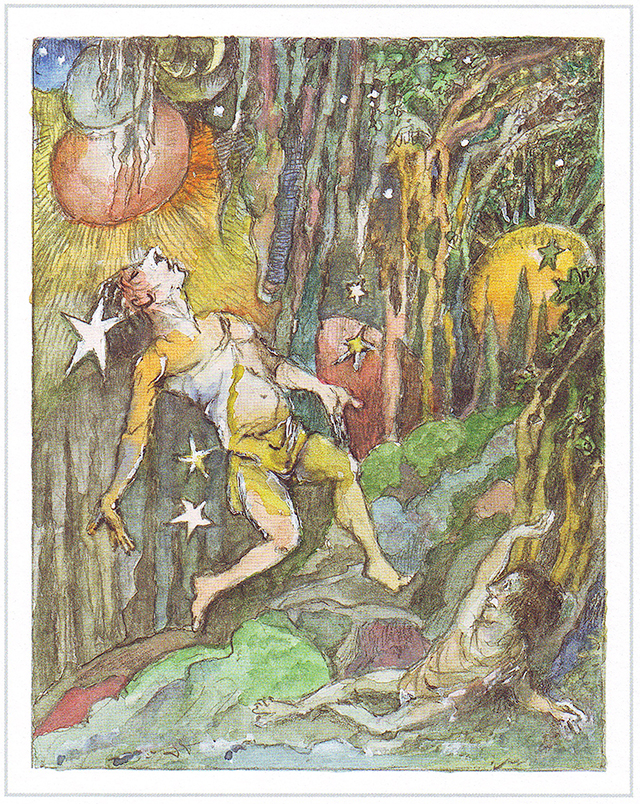

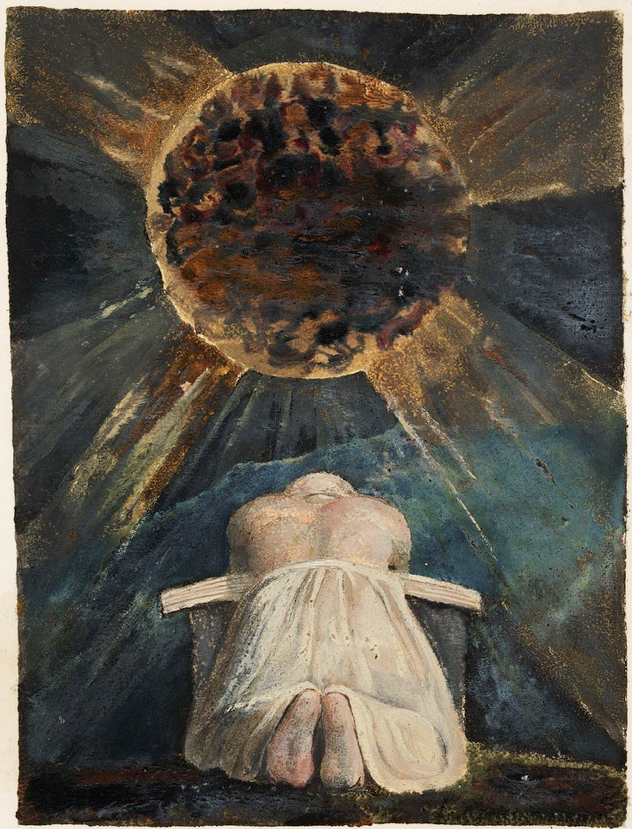

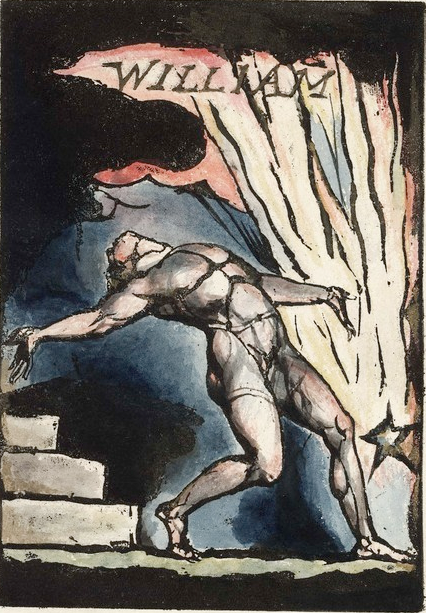

Sendak visually signals the end of innocence and the transition to experience in the next illustration, which compositionally draws on Blake’s depiction of himself in Milton (c. 1804-1811). By modeling Jack’s pose after the figure of ‘William’, leaning backwards at the waist with his arms in a cruciform pose (a pose that Blake uses to denote sacrifice), Sendak is not only drawing parallels between ‘Jack’ and ‘William’ but also invoking what is a transformative moment in this particular illuminated book. In Milton, this illustration depicts a revelatory experience for the narrator that marks a transition from one perceptionary state to another, a complex and more visionary state involving the amelioration of the titular Milton into the poetic consciousness of Blake’s narrator.

|

|

|

Blake, Plate 29, Milton copy B (1811) |

Sendak, My Brother’s Book (2012), p. 9: “On a bleak midwinter’s night” |

Blake, Plate 33, Milton copy B (1811) |

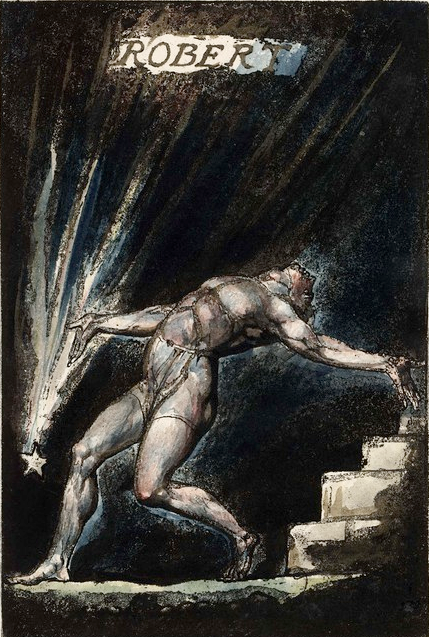

Like Blake, Sendak also provides a counterpart to Jack’s cruciform pose with Guy’s mirrored pose on p. 15. On plate of 33 Milton, Blake provides a counterpart to the illustration of ‘William’, depicting ‘Robert,’ Blake’s brother, in a mirror pose. In both designs, stars are falling into their right feet. Compositionally, Sendak’s illustration on p. 15 seems also indebted to Goya’s Saturn Devouring his Children (1819-22/3).

|

|

Goya, Saturn Devouring His Children (1819-22) |

Sendak, My Brother’s Book (2012), p. 15: “Into the lair of a bear” |

Sendak’s use of these particular poses suggests similarities between Jack and Guy’s fraternal relationship and William and Robert’s. While Robert Blake died at 24, he became a source of creative inspiration for Blake. In 1788, a year after Robert’s death, Blake claimed that his brother visited him in a dream and gave him instructions for illuminated printing: the method he used to create his illuminated books. Sendak’s use of these specific poses hints at a similar creatively productive relationship between Sendak and his brother.

Page 11: Sendak’s depiction of Jack and Guy separated by a sublime landscape (tempestuous ocean, mountains of ice) invokes particular aspects of the narrative trajectory of Blake’s mythopoetic system. For Blake, the fall comes through division, the splintering of a unified entity into enclosed selfhoods. Once separated these selfhoods, which Blake calls ‘Zoas’, typically remain closed off from each other, perceiving existence through limited, subjective vision. Sendak’s depiction of one brother in profile, hands covering his face, while the other brother is frozen behind a wall of ice, suggests the negative impact of subjective perception or, as Blake would call it, single vision. Sendak also gestures to way that Blake conceived of the transition from youth (innocence) to adulthood (experience) as fundamentally about loss. The two brothers have lost each other, their perceptions of each other as well as, by implication, their innocence.

|

|

Blake, America A Prophecy copy E |

Sendak, My Brother’s Book (2012), p. 13: “While Guy wheeled round in the steep air” |

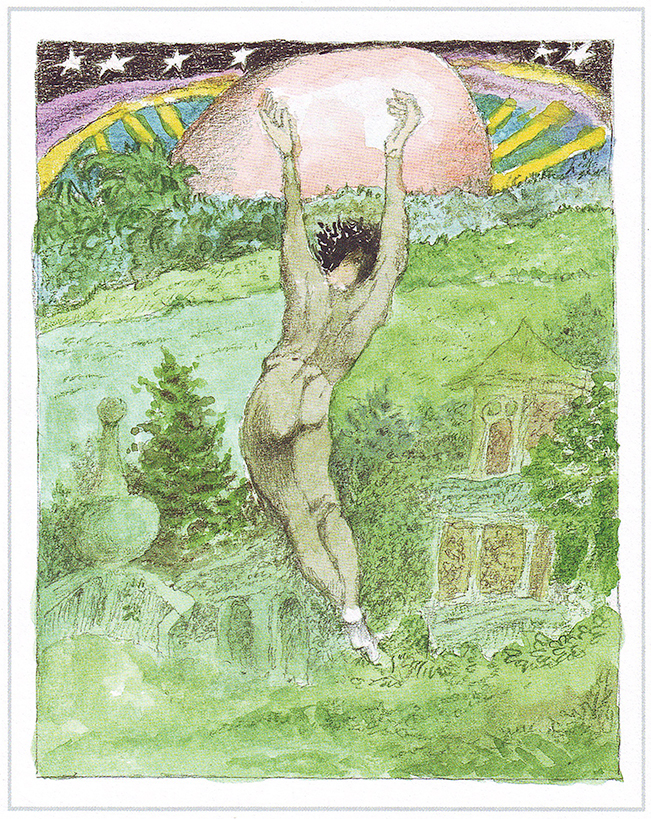

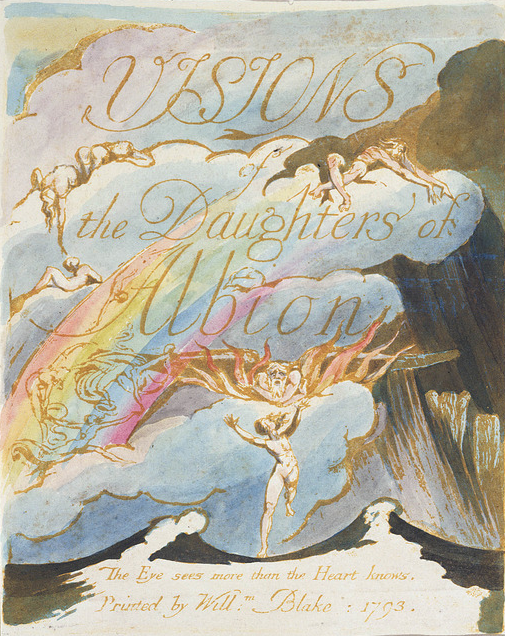

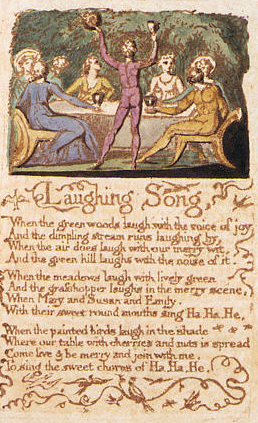

p. 13: For the composition of the central figure, Sendak draws on Blake’s frequent use of clothed (skin tight, all-in-one suits) or nude figures with arms raised, typically in an elevated cruciform pose (the symbol of Christological sacrifice), and appearing to ascend. In ‘Laughing Song’, from Songs of Innocence Blake depicts a young boy, facing away, with arms raised. The title page of Visions of the Daughters of Albion has a nude figure facing forward with arms raised, while we see variations of this figure on the title pages of America and plate 2 of VDA, and Moses Indignant at the Gold Calf. With the possible exception of America, these figures inhabit or represent the realm of innocence. Sendak suggests that this brother has yet to make the transition to experience by depicting Jack in a pastoral setting.

|

|

Blake, Songs of Innocence |

Blake, Visions of the Daughters of Albion copy A (1793) |

|

|

Blake, Visions of the Daughters of Albion |

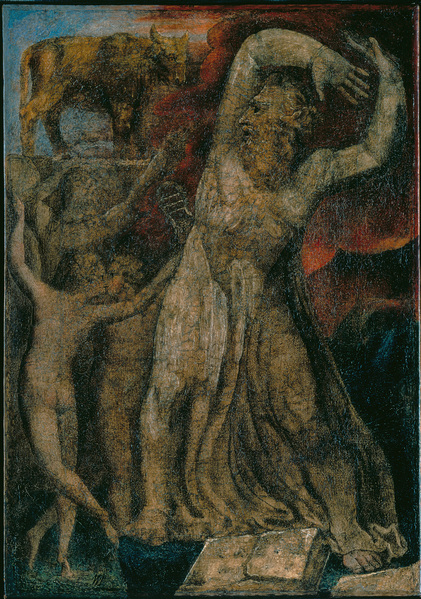

Blake, Moses Indignant at the Gold Calf (1799-1800) |

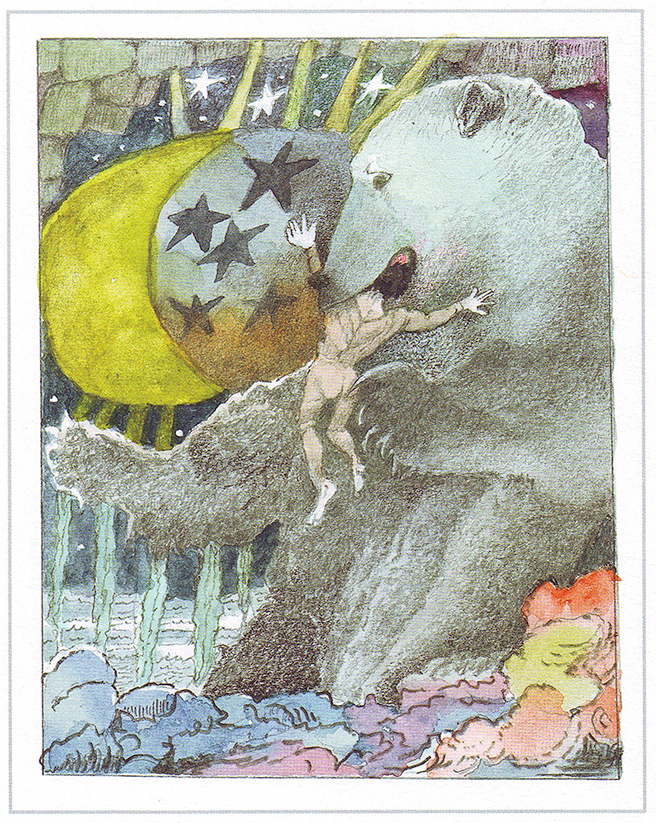

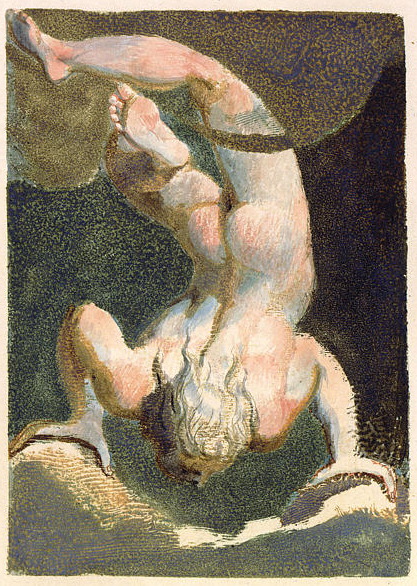

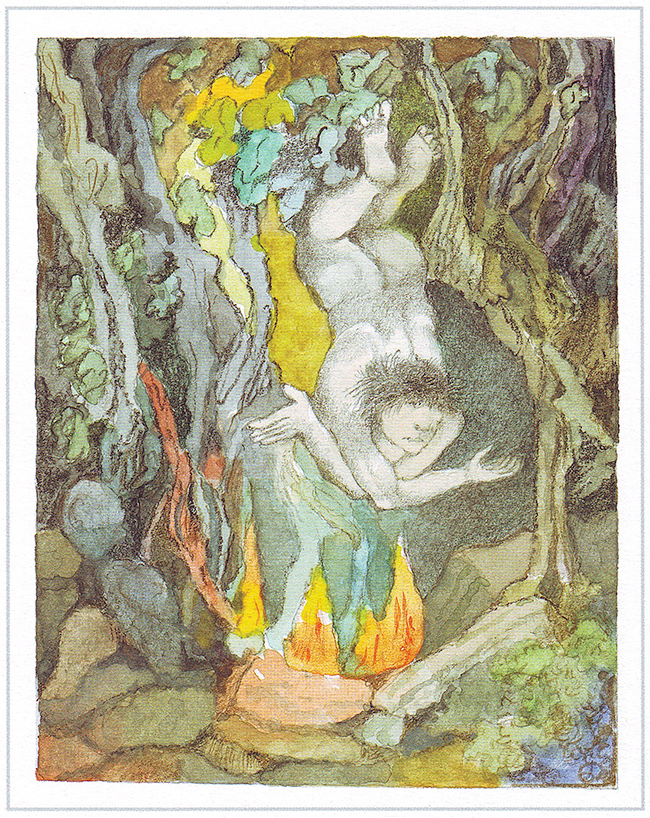

pp. 19/23/29: Sendak’s depiction of Guy diving ‘through time so vast’ on page 23 draws on Blake’s depiction of a muscular nude (possibly Los) diving into an abyss. There are numerous cosmic journeys in Blake’s poetic oeuvre, such as the narrator’s journey from caverns to the far reaches of the universe in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and Milton’s journey from eternity to Blake’s cottage in Milton. In Blake’s design, the figure is holding onto rocks, which denote material existence. Sendak’s depiction of figures partially obscured by horizontal lines on pp. 19/29 recalls Blake’s use of this technique in The Book of Urizen to suggest containment.

pp. 19/23/29: Sendak’s depiction of Guy diving ‘through time so vast’ on page 23 draws on Blake’s depiction of a muscular nude (possibly Los) diving into an abyss. There are numerous cosmic journeys in Blake’s poetic oeuvre, such as the narrator’s journey from caverns to the far reaches of the universe in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and Milton’s journey from eternity to Blake’s cottage in Milton. In Blake’s design, the figure is holding onto rocks, which denote material existence. Sendak’s depiction of figures partially obscured by horizontal lines on pp. 19/29 recalls Blake’s use of this technique in The Book of Urizen to suggest containment.

|

|

Sendak, My Brother’s Book (2012), p. 23: “Guy slipped dutifully into the maw of the great bear” |

Blake, Plates 14 and 4, The Book of Urizen, copy A (1794) |

p. 31: Sendak returns to the pastoral in this design, with the slumbering brothers in poses that compositionally echo the frontispiece as well as Blake’s numerous slumbering figures. The brothers are clothed again, in what appear to be flowing semi-transparent robes that draw on Blake’s regular use of diaphanous or semi-transparent robes in his illuminated books and watercolour designs, including his illustrations to Milton. While Sendak sets the brothers in a pastoral realm, this seems to be a different from that depicted in the frontispiece and may relate to Blake’s illustration on plate 19 of Jerusalem: a realm of soft delusions that numbs creative agency.

|

|

Blake, Mirth (1816-1820) |

Blake, Plate 19, Jerusalem, copy E (c. 1820) |

All Blake images are from the William Blake Archive. All Sendak images are from his My Brother’s Book (Michael di Capua/HarperCollins, 2012).

Mark Crosby is co-author, with Robert N. Essick, of the first critical edition of William Blake’s Genesis manuscript (University of California Press, 2012) and is co-editor of Re-envisioning Blake (Palgrave, 2012). He is Assistant Professor of English at Kansas State University, and the bibliographer and associate editor for the William Blake Archive, the largest and most comprehensive free to access digital repository of Blake’s works on the web.

Gregory Maguire

leda

Pingback: Maurice Sendak & William Blake | Album '50'

Morton Paley